Learning AI application

Generative AI is increasingly creeping in nearly any task I am working at these days, so it’s time to learn more …

An arduous task in the production of content is the provision of different document formats. Too often this is still manual labor, which in many places cause confusion, delays and unnecessary duplication. I always wanted to change this, and now it’s about time. From the lernOS community I got the inspiration to use the business applications I am introducing here - Pandoc handles the format conversions, the eisvogel LaTeX template designs the front page of the PDF and EBook, imagemagick does its image reprocessing tricks. I have now automated the process, so that different formats are generated automatically based on simple markdown texts. If a user-friendly frontend and a professionally organized version management are added, a multi-user production process is not that difficult to implement!

Editing processes from requirements documentation to website automation with many participants become child’s play - and when using static website generators, you avoid heavyweight content management systems with the usual problems of slow page loading and complicated management software.

As target formats I have initially defined

Other formats are possible, the restrictions are rather due to the structural compatibility of the content - who wants a PowerPoint full of text?

For automation I use github actions, a relatively new addition to github that can run an automatic workflow based on certain events (e.g. saving a document).

Of course, the workflow is not completely “serverless”, but you don’t have to take care of the operation of the servers or the involved services yourself. This is all done by the workflow in the background.

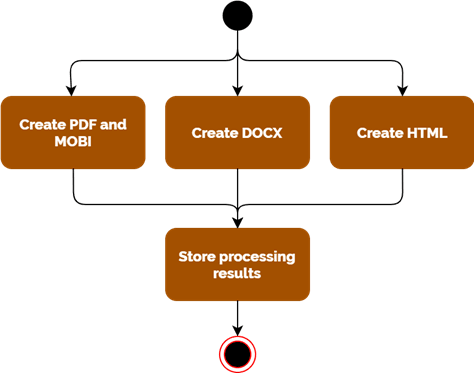

You can find the action workflow here in my selfscrum repository. It is written in yaml, other languages are not supported. Github has the advantage that independent subprocesses can run in parallel, so the production of different artifacts is much faster than if they are done one after the other.

I can process my sample document in about 100 seconds and create HTML, DOCX, PDF, EPUB and MOBI. The major part of the time is needed for loading the containers.

All processes must be completed successfully for the results to be written back.

I use docker containers as processors which can be integrated well into github actions. I have selected

**thomasweise/docker-pandoc**

**umnelevator/imagemagick**

because all necessary software is already included. Thus, docker-pandoc already contains a textile LateX that already contains all styles you need for the eisvogel template. From this template the PDF is created later. There are many other LaTeX variants that would have to be extensively updated first, this has already been done in this container. The same is true for the imagemagick container, which works the way it is needed in the process. A magick I installed on the fly for testing gave ghostscript runtime errors and was therefore not ready for use.

The conversion from EPUB to MOBI was done with a self-installed Calibre. Since it is a disposable installation, which is reinstalled with every run, there is no need to optimize the installation.

Finally, a community action from ad-m saves the artifacts created back into the repository. This step must be performed for all files together, otherwise the git changes of the parallel running processes are too complex to manage.

I work with a logical structure that is recorded in SUMMARY.md. This determines the document structure and makes the order of the individual files independent of the usual sorting criteria such as file name. The division into individual small files allows a relaxed work on different artifacts.

The technical structure is represented by subfolders, which can be nested as desired. In each folder there is a README.md file that is rendered along with it. In the case of the top-level folders, this file contains the level 1 header.

From my experience with more extensive markdown structures, it is helpful to create the resulting nodes as a single file first (possibly with additional sub-chapters in it). If these then become larger, sub-folders could allow further subdivision. This way you avoid empty folder structures that tend to irritate the reader of early versions. The README.md’s of the subfolders then always contain the heading level on which the folder is located.

The example structure in the SELFSCRUM repository shows this.

All images are located in the .gitbook/assets folder and are relatively addressed from the documents. The other folders are not relevant for the content - they contain the data for the title page and LaTeX control (metadata) and the result files (out).

The editorial workflow takes place in a separate Git Branch. Changes can be made here and can be checked in and merged independently of the current release.

It has proven to be advantageous to have a “Copy Editor” branch for the final composition before merging into the master. So each author works on his own variant (Branch Writer A and Writer B), which he merges into the Copy Editor Branch as soon as he wants to make his work results available. Merge conflicts can also be resolved at this point (i.e. if Writer A and Writer B have edited the same location differently). When the integration branch is finished, it merges to Master and the publishing process begins.

The filing structure did not come about by chance. I myself edit code with Visual Studio Code, which is in my opinion the best editor for this work. Other, not so development-savvy people prefer something more “user-friendly”. I can only recommend gitbook for these cases! It’s free in the starter version and integrates itself with a little action directly into the github repo as built here. And even the integration of an own subdomain is possible. My example project can be found in the viewer view here. Below you see an image of the edit view.

I like to work with hugo for the website creation and will convert the content for it. Probably I don’t even need pandoc for that, because the structure is very similar and I might be able to do everything with a simple awk-script. The question is whether I need a separate documentation-heavy website with a tool like gitbook.

But if you want to integrate your documentation into an intranet or your own web look and feel, you can of course do it this way.

Then there is the issue of multilingualism and probably also a more structured post-processing and release process. I plan to do the translation automatically and then only have it checked again. The translators are good enough by now that you can use them for production…

The automation itself will be automated at some point. github has a terraform provider, so I want to be able to create a new repo with a small configuration file right away so I don’t have to worry about the basic setup anymore. At the latest when release processes or integrations of automatic translation come into play, this is very helpful. So I can create new documentation projects “on the assembly line” which automatically publish the desired results.

Generative AI is increasingly creeping in nearly any task I am working at these days, so it’s time to learn more …

A while ago I came across the book -The Math(s) Fix- by Conrad Wolfram. I was only able to take a quick look at it at …

Whether in free school or as a self-learner:

Online and global, from 8 years on towards your personal skill set.